Basel-based fechtmeisters are rare. Across a fifty-year sample of council records I’ve reviewed in Strasbourg, only two fencers from Basel showed up to practice in the city between 1540 and 1590: Hans Baumgartner and Joachim’s brother Hans Jacob Meyer, both of whom were messerschmidts. This lack of Baseler fechtmeisters exacerbates certain mysteries, making it much harder to speculate about who might’ve provided an early fencing education for Joachim Meyer and the two Hanses. Luckily, we were able to identify a fechtmeister who was active in Basel during Joachim’s early life: Hans Rorer.

All sources below are available (transcribed and translated) in our Hans Rorer research document.

Hans Rorer…

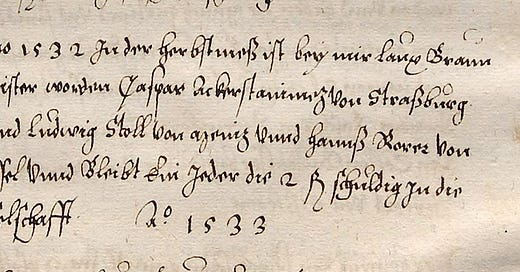

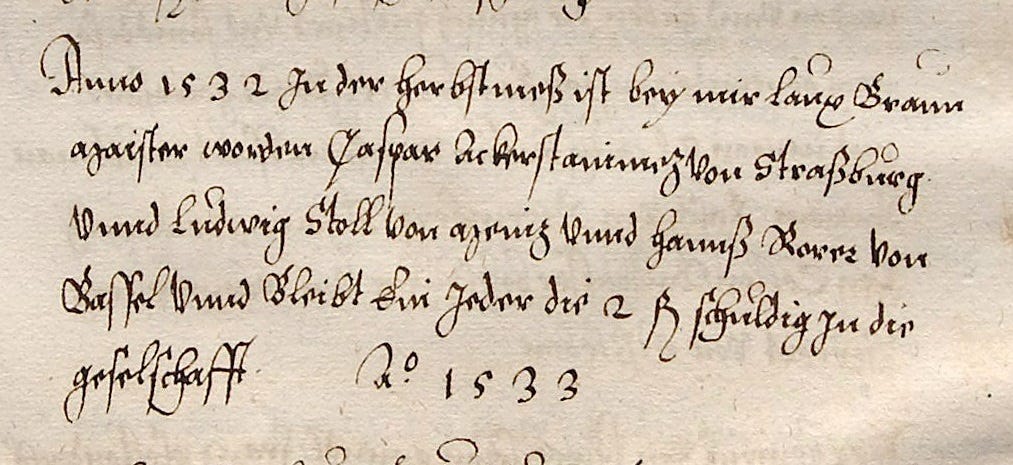

…was a printer (drucker) and fencing master who appears in the Basel records from the early 1530s until about 1546. He is recorded within city court documents, parish records, and other local archived material, but his earliest dated appearance comes from the so-called Hans Medel Fechtbuch, a compilation of various fencing-related texts. He is reported as having received the title of a “Master of the Long Sword” at Frankfurt in 1532, putting him into the inner circle of the Marxbrüder.

This is so far the only source which directly connects Rorer with fechtschul-related fencing culture, but many of the council books for this early half of the 16th century in Basel are not digitized, and thus remain unreviewed.

In Basel, his appearances range from mundane to extremely interesting. Starting with the more straightforward sources, he had at least one confirmed child (Hans Jr.) baptized at the St. Martin parish on June 14th, 1537. There are two more baptisms which list a much more vague “Hans the Printer” as the father, but currently these cannot be tied securely to our Hans Rorer.

Beyond these parish records, Hans Rorer shows up in the city’s account book in 1542, where he is recorded as having paid a fine of eight pounds. The margin names this as a “war council fine”, possibly relating it to the outbreak of the Italian War of 1542-1546, but not much more can be said at the moment.

In 1543, Hans Rorer was involved in a conflict with wind instrument players. Finally in 1546, he applied for the job of gerichtsknecht (court servant), maybe indicating a career change. This application is mentioned in secondary sources such as the Geschichte der Leibesübungen (“a history of bodily exercise”) and currently marks his last verifiable appearance. This is where the trail runs cold for Hans Rorer. Joachim would only be nine years old in ‘46, leaving us with twelve years until Hans Baumgartner officially received the title of fechtmeister from the Basel council in 1558. Extending the known record for Hans Rorer into the 1550s, or establishing a different fechtmeister in these interim years would perhaps allow us to eventually associate a local teacher with Joachim Meyer.

A Drunken Brawl

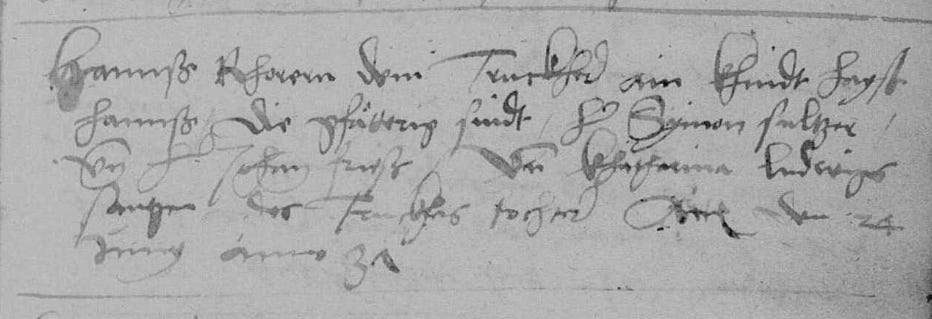

And now for something completely different. The most interesting record for Hans Rorer, and the only other one I’ve found which names him as a “vechtmeister,” is one from the Kundschaftenbuch (report book) dated March 29th, 1538. The Kundschaftenbuch consists of witness testimonies collected in the wake of various crimes. Hans’ testimony involves him getting beat the fuck up! It is one of multiple accounts about a fight which broke out at a tavern, where Hans was having a drink with some of his printer pals.

Hans Rorer the fechtmeister says under oath, that on last [unclear] Sunday his journeymen - two printers - invited him and others to dine. With them he went to the “Bären” in Aeschenvorstadt, where he spent time and was in good spirits.

And after this [unclear] and when he looked at his watch, he wanted to go home and asked if none of his journeymen wanted to accompany him. Thereupon Hans Ruter and Severin, both journeyman printers, rose and went with him.

And as the witness went down the steps, nobody stood yet by the steps[?], but as he reached the door, he looked behind him and saw Martin Schölle rise from the table and stand up.

Then it reportedly happened that Hans Ruter tried[?] to walk past and asked if a good journeyman wasn’t able to pass. Schölle presumably answered that a good journeyman shall pass, but a different one at the table - supposedly a brick mason or carpenter - reportedly screeched and cursed, also immediately drew from his sheath. He was the one who made noise, but how and by whom Severin was struck in the neck (for it happened in the house), he cannot properly say, for he neither saw it or was present, but stood outside in front of the door.

But as they came out (the carpenter was the first to rush towards him) Schölle, Hans Küsser and one named Weingarten of Bern inflicted upon him the strikes [= streich] and stabs [= stich] - even though he had spoken no evil word to them. He also does not know where Severin was wounded in the knee, because as soon as the witness [Rorer] returned to his house, he wasn’t able to stand up anymore, until finally a journeyman cleaned his face, this he permitted.

He [heard?] that Severin “fell into a wheel” [= was surrounded?] where he was struck, and Schölle, Hans Küsser and Weingarten attacked them fiercely.

The witness also doesn’t know of any bad words exchanged between them. On the other hand, he has heard since then that there was reportedly a Dutchman among the printers, who went to Schölle and his company, gave them to drink. They asked him if he was a landsknecht, he said yes, thereupon Schölle reportedly hit him in the face etc.

Rorer and his journeymen received a real drubbing, with Hans needing his face cleaned (likely of blood) and being too weak to stand after stumbling home. If this incident resulted in a legal conviction, it is likely recorded within the Urteilsbücher (verdict books) of the city court, which have yet to be investigated. If the Severin of this source is identical with a “Severin Rychwin, bookbinder” who received a warm farewell from the Basel council in 1545, Severin might have survived his injuries.

As to where this fight took place, there are at least two properties in the Aeschenvorstadt (Aeschen suburb) which had the name “zum Bären” applied to them, with Aeschenvorstadt 67 being a high possibility for the tavern in question. This puts our brawl at approximately this location in modern Basel, which is a short distance south of where Joachim’s father Jacob lived in the St. Alban-Vorstadt.

Hans Rorer himself might have lived in the Aeschen suburb - there is a later property record under his name at Aeschenvorstadt 44. However, it lacks a job title and there is no earlier record for a Hans Rorer at this location. Additionally, there is a Hans Rorer, miller, who lived in St. Alban and might have possibly owned property around the city.

The underlying cause of the incident is unclear. The conflict might’ve kicked off after Schölle learned that one of Rorer’s drinking buddies was a Dutch mercenary. Maybe Schölle had bad blood with the landsknechts, didn’t like Dutch folks (how dare he, as a Dutch-American), or was just totally shattered and looking for a fight. Whatever the reason, this record is unique. It seems that Hans Rorer’s “vechtmeister” and “master of the long sword” credentials didn’t pay off after a couple glasses of wine. “In duh Streetz” HEMA nerds, read up!

Conclusions and Outlook

Hans Rorer currently sits as a top candidate for the fencing master of Joachim Meyer’s youth, mainly due to being included in Basel records while Joachim was living there. With a general lack of names that can be placed near Meyer, Meyer researchers tend to grasp at straws or look for the smallest of toeholds. While we presently cannot extend Hans Rorer’s life into the 1550s, there are cases such as that of a young Georg Scheurl who was training with a fencing master as early as the age of six!1 Perhaps it isn’t that far-fetched that a young Joachim Meyer might have come into contact with Rorer, swinging swords as a kid (which I would have much preferred to piano lessons at his age).

Rorer’s profession as a printer is of particular interest. It would’ve put him shoulder-to-shoulder to other related industries, such as the papermaking industry into which Joachim’s family was embedded. He possibly even knew Jacob Meyer, due to the elder Meyer’s work as a papierer. We currently do not know much about Rorer’s activities as a fencing teacher in Basel, however he held the highest certification of the Marxbrüder. If he acted as an early influence, it would be another facet with which to explain Joachim’s fairly unique dive into publishing fencing works.

With the most notable fencing master of Joachim’s childhood (and possibly youth) being a printer, with his own father’s work as a papermaker and his family’s ties to various figures in the book-making industry in Basel, the idea of producing a printed fencing book might have come naturally to Joachim, drawing upon experiences made in this environment. Think of a modern HEMAist with a background in video production or coding leveraging that experience to crank out high quality instructional videos or making sites like HEMA Scorecard.

There is still much to discover about Hans Rorer. Most of the council, court, and guild records during his lifetime are not digitized and have not yet been reviewed. Additionally, he seems to have not been a big player in the printing industry in Basel. There have been extensive studies on 16th-century printers, and Rorer hasn’t appeared in any of the publications on the subject I’ve explored. For example, this long list of "Basel printers and publishers" lacks Rorer, an omission that seems habitual in the literature. It is likely that he was just a workaday printer, possibly printing calendars, playing cards, or other day-to-day items rather than the long-lasting notable written works and books which famous printers like Johannes Oporinus created.

Finding sources that put Hans alive during the 1550s, when Joachim and Hans Baumgartner would’ve been teenagers, would strengthen the possibility that he was their teacher. There is an argument to be made (also presented in Geschichte der Leibesübungen) that the role of a “fechtmeister” was more codified in Basel than in Strasbourg. This social position (Stand) was directly conferred upon Hans Baumgartner in 1558. I could see Hans Rorer passing along his position to Baumgartner as he got older, or possibly leaving his seat vacant after dying. However, after dozens of hours of digging, I have yet to find more records than those which exist within our Hans Rorer Research Collection document.

Fingers crossed that more Rorer rears its head soon!

Thank Yous

Infinite thanks to my research partner Miriam for all of the help and hard work in transcribing and translating the records related to Rorer. The Kundshaft record especially was complex, scribbly, and difficult to polish up, and I cannot thank you enough! Additional thanks to Alain Grimm, Irtenmeister at the Basel Safranzunft for looking into Rorer-related records for their guild, and thanks to the Basel archives for the digitized records that enabled these discoveries!

Flesh and spirit : private life in early modern Germany

by Ozment, Steven E, page 119-120