Hans Baumgartner, Messerschmidt and Fechtmeister of Basel

A friend or rival of Joachim Meyer?

A messerschmidt and fencing master of Basel born in the 1530s. Sound familiar? No, it’s not our old friend Joachim Meyer, but rather another fechtmeister from along the Rhine: Hans Baumgartner (ca. 1530s - 1590s). Hans shared much in common with Meyer: close birthdays, a city he was raised in, a profession, and a love for fencing. However, Hans’ fencing career took on a different significance in his life than for any of the other fechtmeisters we have explored, granting him both citizenship and official recognition in Basel. Using a combination of primary and secondary sources, we will explore the life and career of Hans Baumgartner, from his family to his professional fencing and mysterious imprisonment.

All translations were completed by me and/or my research partner Miriam, and you can check them all out here in our research document!

Fencing Life

Hans Baumgartner does not currently have an extensive list of fechtschul attestations to his name, but the ones we have are quite interesting. He was recorded as fencing in at least three cities: Bern (1558), Strasbourg (1558, 1568) and Basel, where he may have held status as the fechtmeister of his home city.

On February 11th of 1558, Hans received permission to hold a fechtschul in the city of Bern, as evidenced in the Bern archival source A II 214.

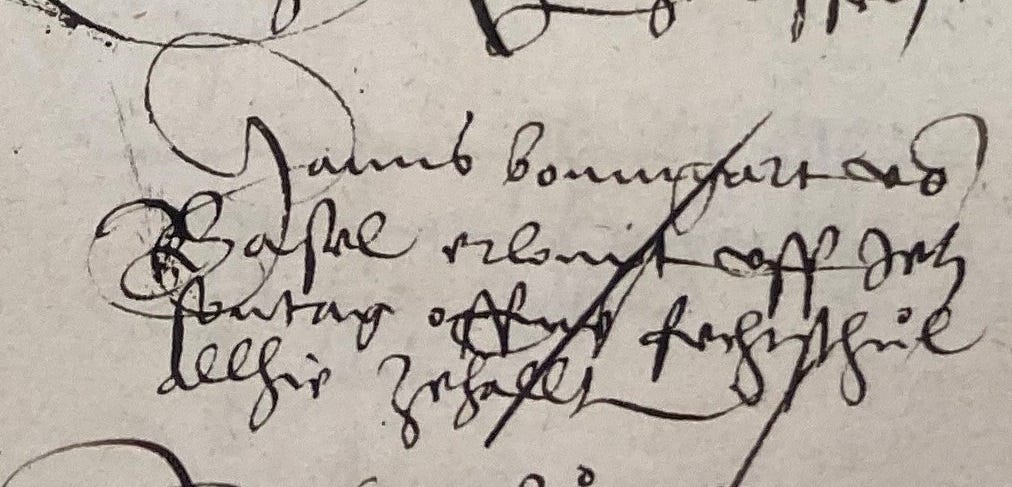

Hanns Boumgart von Basel erlonit [= erlohnt] vff Jetz sontag offne fechtschul allhie zuhallt[en]

Hans Baumgart of Basel endowed to hold here (a) public fechtschul on this Sunday.

Only seven months later, in September, he appeared farther north in Strasbourg. His request for a fechtschul contains his titles of messerschmidt (cutler) and freifechter, mirroring Joachim Meyer and preceding him in the local Strasbourg records by two years.

Hans Baumgarter of Basel, cutler and freifechter, asks to grant him to hold a fechtschul on Monday, wishes to keep himself judicious. Recognized, to be allowed.

These two fechtschul requests might have coincided with the last of Hans’ journeymen years. As a journeyman messerschmidt, he probably traveled widely and fenced wherever he was working.

In December of the same year Hans used his expertise in fencing as the means to acquire citizenship in Basel. This event was recorded in the Öffnungsbücher (“opening books”) of the Basel city council and was noted in various 18th to 20th century publications, such as the Schweizer Heimatbücher and the Geschichte der Stadt und des Lands Basel. The full text is quoted in the 1896 publication Geschichte der Leibesübungen (“A history of sports”) and gives us interesting details about Hans Baumgartner’s life and background:

Anno 1558 (Öffnungsbuch page 181), on Saturday the 17th day of December

Hans Baumgarter was born to the cutler of Wil in the Thurgau, was brought here to this town Basel by his father - who moved here and has been an inhabitant without citizenship here - and has been educated here, subsequently followed his craft and learned the Free Art of Fencing. He also offered himself now before an Honorable Council, if it is pleasing to our gracious gentlemen to grant him the schul and the social position (Stand) of a fechtmeister, so that he may then hold the schul after the custom of the sword. And following accommodating acceptance of his request he has been gifted citizenship with good grace and also swore the citizen’s oath as an accepted citizen, as usual.

Unlike Meyer, Wygand Brack, and even the extremely prolific Georg Kellerle who all had to obtain citizenship through marriage or purchase, Baumgartner was able to get his foot in the door through fencing itself (along with a prior life in the city). With the way this note is written, and with the additional information from Nenninger’s letter (more on it below), it seems that the position of “fechtmeister” was a much more formal one in Basel and perhaps more closely integrated with the local city council - in stark contrast to Strasbourg, where the Council of XXI avoided formally regulating fencing inside the city.

Baumgartner’s final known fechtschul request occurred in December of 1568 in Strasbourg and mentions one of his more noble connections:

Hanns Baumgarter, citizen at Basel, a fencing master, lets Dr. Knader report that he has been summoned to Heidelberg by Count Palatine Christoph, the Elector's son, (he) is planning to hold a fechtschul here prior to this. Requests to allow him such on Monday.

Recognized and he is allowed but that he shall (not) take more than one heller.

Count Palatine (Pfalzgraf) Christoph was a member of the house of Wittelsbach and the youngest son of Elector Frederick III. He was brother to Johann Kasimir, to whom Joachim Meyer dedicated his famous 1570 fencing manual. In 1568, Christoph was seventeen years old and studying at the university in Heidelberg. He eventually died in 1574 as a combatant in the Battle of Mookerheyde.

Why Baumgartner was summoned remains a mystery, even after digging through some of the extensive university records in Heidelberg. After contacting the University Archives at Heidelberg, we were informed that Baumgartner does not appear in any of the registers and was thus perhaps directly employed by the electoral court. His summons was likely not a long affair, with his wife continuing to live in Basel and having a child born less than a year later in 1569.

The Baumgartner Family

Hans’ citizenship grant identifies his father as a resident without citizenship (hintersass) and as having come from the city of Wil in the modern canton of St. Gall (the name Thurgau was formerly applied to the entire Thur river valley). For more information on the Baumgartner family, we can turn to the genealogical research of Dr. Arnold Lotz. More information on Dr. Lotz is available in our article on Joachim Meyer’s family and all relevant sections of his work can be found in our research document.

According to a Basel source identified by Dr. Lotz, Hans’ parents Hans Sr. and Dorothea were married at Bettwiesen, a village near Wil. The parish at Bettwiesen adopted Reformed Christianity in 1530, but was forcibly re-converted to Catholicism in 1542, with Reformed Christians being expelled. Hans Sr. moved his family to Basel at some unknown point and raised his children there, but we currently do not know whether this move happened against the backdrop of a religious conflict, as the timing would imply.

After working as the stubenknecht (the person responsible for the guild tavern) for the Rebhaus guild in Basel, Hans Sr. likely died in 1561. In his excerpts, Dr. Lotz records Hans becoming legal representative for his younger sister Verena in November, likely indicating a change of guardianship. Hans also had a brother named Ulrich who was a very…virile man. According to the genealogical records compiled by Dr. Lotz, Ulrich would go on to have 16 children, some of whom would have their own children recorded as late as the 1660s!

Hans’ exact birthdate is unknown to us, but we can approximate it using other life events of which we have knowledge. After stints in Bern and Strasbourg, he returned to Basel in late 1558. In 1559, he bought membership in the smith’s guild at Basel, becoming the first entry in the “book of admissions” for that year. Hans had his first child with his wife Chrischona Meyer (no known relation to Joachim Meyer’s family) in April of 1561.

Using these facts, we can hypothesize that Hans was likely around the same age as Joachim Meyer, who was married in mid-1560 and born in 1537. Hans died sometime before 1593, approximated using a reference to his wife Chrischona as a widow from this date.

Hans’ children

Hans had at least four children with Chrischona: Hans (1561), Dorothea (1564), Abraham (1565), and Anna (1569). Dr. Lotz notes two more children in 1571 and 1580, but these have been more difficult to validate.

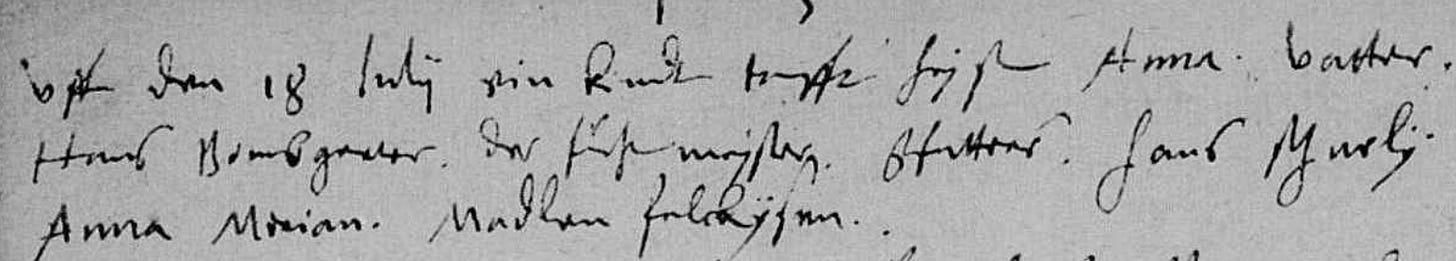

Two Hans’ children have interesting inclusions within their baptismal records. He is identified as “Hans Baumgarter der Fechtmeister” for the baptism of his daughter Anna in 1569, reflecting his status in Basel.

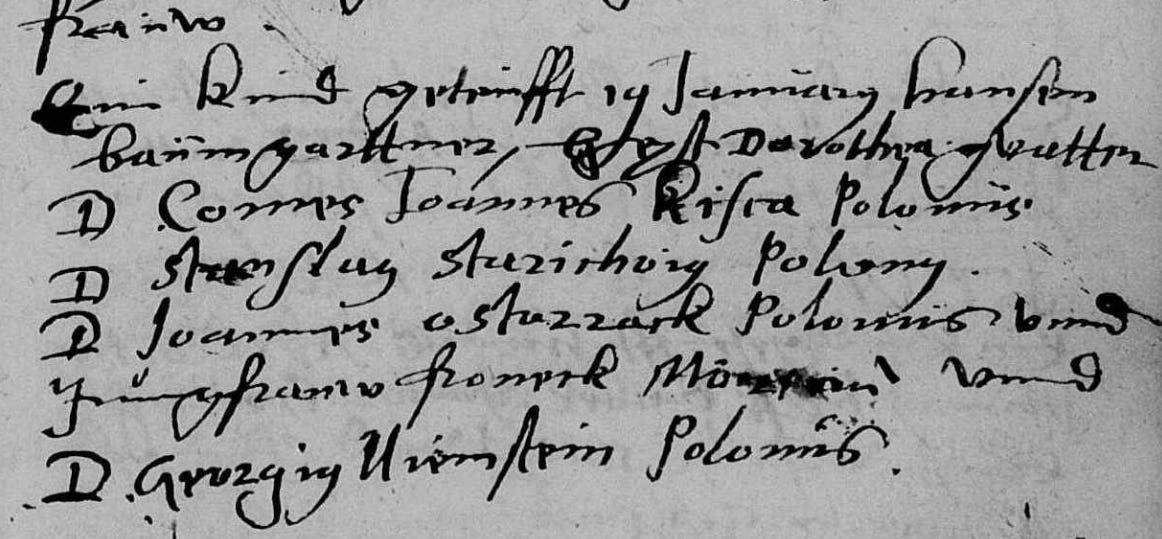

More strikingly, the record in 1564 for his daughter Dorotha is a veritable who’s who of godparents, including a large number of Polish-Lithuanian nobility who were in Basel at the time, studying under the scholar Celio Secondo Curione. These include:

Jan Kiszka, son of Stanisław Kiszka

Georgiy Niemsta (written as “Niemstein”)

and Veronica Merian of the prolific Basel Merian family.

More information on these nobles and the circumstances under which they studied in Basel can be found in the amazing article Die Hochzeit polnischer Präsenz in Basel. I hypothesize that Hans acted as a fencing instructor to them - there is however no primary source which directly confirms this relationship.

Andres Nenninger and Imprisonment

During Miriam’s recent trip to Basel to investigate Joachim Meyer’s family she was able to review the B39 archival record, a collection of various loose documents related to fencing activities in the city. It contained an undated letter written by Andres Nenninger of St Gallen, a fencer who also appears in the Strasbourg Council of XXI records and would request permission to hold fechtschul multiple times: in 1570, twice in 1571 (fencing alongside Centurius Letsch and Wolf Brand), and once in 1573.

In this letter he petitioned the local council at Basel to allow him a fechtschul in the light of Hans Baumgartner’s imprisonment. It is implied that Hans’ absence and the “lack of a master” has been disruptive to the normal course of fencing activities in the city. The translation below was completed by myself and Miriam, and is presented in full with the most interesting bits bolded.

Noble, rigorous, steadfast in honor, pious, circumspect and wise, gracious, also favorably dear Gentlemen, to Your Graces and the Reverend[?] (Seiner Ehrwürden) belong my subservient and willing service, and what I can favorably and well do, at all times in advance.

Gracious Gentlemen, since Your Graces and the Reverend have been moved out of innate goodness to assist those who have been noted with knightly art and honest-living morals, and (have been) confident that they thus contribute to the common benefit (as was necessary):

Since I, by God's Grace, have learned the knightly and noble art of fencing through lengthy exercise, also effort and toil; and by the benevolence, love and favor that Your Graces and the Reverend (show) to the mentioned art I have been swayed to travel and make myself available in this widely-famous city of Basel, with Your Graces' permission to hold a free public fechtschul.

It is my subservient and sedulous request that Your Graces and the Reverend may graciously grant, allow, concede and permit me - a neighbor and born Swiss Confederate - to prepare and hold a free public fechtschul on the [unclear] day. So that I can redeem and take to hand my swords which I deposited and pawned out of lack of a master, partly because of the imprisonment of Master Hans Baumgartner the fencing master, who finally advised me eight days ago to subserviently present now my plea and request to Your Graces.

It is now my turn to obligingly earn and await in consoling hopefulness, in all subservience and obedience, untroubled[?] by my small means, a gracious answer in consideration of our ancient shared native country and my considerable destitution, by Your Graces and the Reverend, whom the Almighty shall graciously keep in happiness and preserve.

Yours, the Reverend’s

Subservient, willing and obedient

Andres Nenninger of St. Gallen, weaver and freifechter etc.

Andres has pawned his swords, given up fencing, but has been given advice by Hans to ask the Basel council to allow him to fence once more. It sounds like a simple fechtschul request in the letter, but given the added weight to Baumgartner’s official role as fencing master, it might function as a request to take over Baumgartner’s position in Basel.

The nature of Hans’ imprisonment is still a mystery. The letter uses the word Gefangenschaft, which according to Miriam might imply more than a simple jail term (where expressions like “put into the tower” are often used). Our fechtmeister might have been locked up under more serious circumstances. The lack of date on the letter doesn’t help any, as knowing if it was after Hans’ summons to Heidelberg in 1568 would allow us a narrower scope to search.

Further Research and Conclusions

We have quite a lot of historical records revolving around Hans Baumgartner, our fechtmeister of Basel. However, with details such as his social position of fechtmeister in the city, his connection with nobility both local and foreign, and his impactful imprisonment, I would expect even more to exist about his life. The Basel and Bern archives have far fewer easily-reviewed digitized documents than Strasbourg, and remain largely unexplored compared to Strassy’s extensive online presence. Digging into council records and letters in these cities would likely yield even more fruit, and remain a point of future emphasis.

Additionally, some of the references above were taken from excerpts and quotes. Using these specific references to validate the primary source they cite would add weight to Hans’ life and perhaps point towards additional details. During his time, Hans Baumgartner was another influential fencing messerschmidt along with Joachim Meyer, as two young men of the same generation with a passion for fencing, but ultimately operating in slightly different structures around fencing in the cities they chose to make their home. Joachim turned to books, perhaps because a position as the fechtmeister of a city was not possible in Strasbourg where he settled down, or perhaps he moved there in the first place because Hans got the gig that Meyer wanted. We may never know if they were fencing rivals or friends, but it’s fun to speculate about.

Thank You!!

Thank you to Miriam for your endless amazing assistance in helping me transcribe and translate notes, along with your feet-on-the-ground help in Basel to dig up primary sources. Additional thanks to Dr. Benjamin Ryser from the Staatsarchiv des Kantons Bern in tracking down the Baumgartner fechtschul using a secondary source as a guide and providing expert insight into their archival materials (much more to explore in those books, I hypothesize), and to Dr. Ingo Runde, Archive Director at the Universitätsarchiv Heidelberg for cross-referencing and checking in on our 1568 connection to Hans. Lots of teamwork went into writing this article, and my thanks are infinite!